Collaboration : Skill or Culture

In his editorial, Russ Crawford references the case studies covering collaboration, to contend collaborative working is a learned skill. However, Russ goes further, suggesting other factors are at work, and collaboration may also be a culture. Russ closes by inviting readers to form a conclusion or even suggest a theme not covered.

Author : Russ Crawford

It`s difficult to define, mercurial to measure and widely touted as “something we do very well” in higher education, but true “collaboration” requires both a working definition AND a way to measure or like so many other umbrella pedagogic concepts, it`s likely to be something we THINK we do well but how do we truly know?

Having been an educator in HE for many years across a range of educational and pedagogic contexts and with more years of experience under my belt that is healthy to dwell upon (put it this way, the INTERNET didn`t exist when I was doing my first degree!), the “idea” of collaboration is a well-trodden pathway with traits that are identifiable at a glance but I would postulate that we need much more granularity when it comes to whether collaboration is a skill to be sharpened or a culture to be fostered.

How do we actually “define” and “measure” collaboration?

In HE, we all love a good measurement, whether its learning gain, retention, progression or even…. dare I say it, satisfaction! Like many other working definitions of difficult concepts, it comes down to the distance travelled as a true measure that takes the individual and the surrounding context into account. As educators we build collaboration into our curricula which is where the question of whether it is a “skill” came from in this editorial. There is a tendency to take it as given that HEI`s can not only impart what “good” collaboration is (conceptually and practically) to students but also that it is possible therefore, to get objectively better at it over time. This is the basis for my assertion of “collaboration is a skill” – it is teachable, it is buildable, it is demonstrable and therefore, it is a skill.

Whether you love or loath “collaboration”, there are key immutable skill-based facets that are inherent to it: Group working, reflection, goal-orientated practice and output(s) are each common factors in “collaboration”, which further support my skills-based argument and aid us in developing a skills-centric working definition of collaboration.

The maddening thing is that we do it all the time, but like all good educators, we can`t just rely on a holistic “that`s good collaboration” sage-like chin stroke, we need to evaluate its parameters, its domains and most critically, its efficacy. This is where the counterargument comes to the fore: Collaboration might actually also be a culture!

Stay with me on this one, but when we think of collaboration we think of the “doing” of it, for the most part but what gets eclipsed is often the circumstances within which collaboration takes place to achieve the doing. Arguably, its actually when collaboration goes wrong that we get the most impactful and meaningful learning taking place. We all remember the hard lessons learned from past less-than-ideal (read: catastrophic!) collaboration experience(s) and we circuitously take these cultural lessons into our next collaborative experiences and begin the cycle again. Whilst I still assert that collaboration itself is indeed a skill, the circumstances surrounding collaboration are almost entirely cultural in nature. Groups, teams, networks, learning communities and human traits such as compassion and support are all therefore ALSO “collaboration” in action.

So, there you have it, in the academic equivalent of having my cake and eating it: Collaboration is most assuredly a skill but is it also possibly a culture?

To address this, I draw upon 7 different case studies that were submitted to the Jisc Digital Culture forum who have been curating a case studies collection around cultural norms/expectations and organisational practices facilitating productive and rewarding digital working.

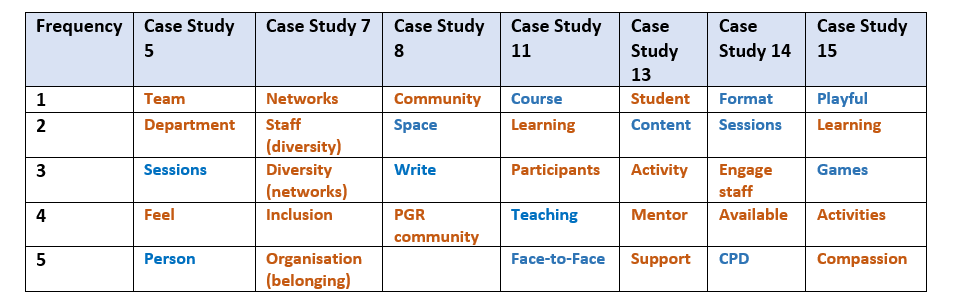

From this, we know the measurement criteria (skill or culture) and all that remains is setting the boundaries of what is and is not, collaboration in practice and how often each appear in the case studies. Dusting off my action research skills, I decided it might be interesting to take 7 of the Jisc case studies with overt collaborative themes, conduct a little textual analysis and then compile results of a “top 5” of the language they use and infer any link(s) to “collaboration” either as a culture or a skill, to reflect upon in this editorial. To make it easy at a glance, the table below lists the top 5 most frequent words (or terms), with those in the tan font identifying “cultural” and the blue font identifying “skills-based” facets of collaboration emerging from my analysis

There were other concepts that emerged from within these case studies that might contextually aid us in further defining collaboration as a skill and/or a culture.

One of the major themes that came forward overtly was a real emphasis across each of the cases studies on sense of belonging, tied both to wellbeing and community. What was loud and clear across all case studies was that there were various iterations of “community”, both for support and for sense of belonging. It appears that the social environment(s) of collaboration plays a critical role in helping or hindering the experience of collaborative working that can impact on lived experience and indeed, reflective experience of collaboration. Harking back to my point above about carrying our collaborative experiences with us cyclically, this would therefore suggest that positive perceptions of belonging are key to iterative successful collaborations. As educators, we have a range of options to help us utilise this information: We can structure and mandate those environments ourselves or we can allow them to form authentically in groups, but I suspect success will come less form the degree of scaffolding we provide in this instance and rather, more from in-group awareness that community and belonging can make or break a collaboration before any work has been done.

Interestingly, whether the context of the collaborations (in the case studies) were physical (i.e., face-to-face) or digital seemed to have an impact on the way collaboration was experienced, both in terms of timescale and engagement / interactivity levels. In essence, the format of the collaboration played a pivotal role in setting the timber of the experience, with many of the group dynamics influenced by that early decision on format. There were positives in both cases to be drawn from across the cases, but a common trait I observed was very much centred on the value of real-time communications for collaboration, regardless of the format of delivery. It was that sense of “live” and therefore, progress that underpins this observation, I feel. There were some interesting reflections around the digital format aiding removal of physical barrier to participation that manifested as both an inclusivity driver as well as an enhancer for the confidence side of collaboration.

It seems from these studies that the key to collaboration in many instances is the environment within which folks can contribute their ideas. Key within this theme was (be that format or group working practice-based) environmental removal or reduction of silos within the collaboration. Drawing on some very convincing inter-professional education literature, this is a core idea that has been orbiting “collaboration as a skill” for a long time and it is reassuring that even in the digital renaissance we are currently experiencing, this remains in play. Freeing individuals from their own professional profiles can be rocket fuel for collaboration, as the individual emerges from behind their professional persona and in doing so, they bring much more to the collaboration as multi-faceted people rather than labels such as “insert discipline student” or indeed, “manager”.

Hand in hand with both the community and environmental aspects of collaboration discussed above, the final emergent theme from my analysis was enablement of choice when it comes to participation and engagement. Whether that choice comes in the guise of mentorship, activities, professional development, or course / session design, it seems that the motivations of the collaborators need to be a consideration when designing or providing collaborative opportunities. This is where reciprocity might aid us, as we lean into what is sometime called obligational computation (i.e., what I owe you and what you own me) in collaborative contexts, as groups learn to (sometime fail to) work together, to reciprocally share information, support, experience, respect and most of all, knowledge.

“So what about digital?” one might ask, and indeed, what difference does it make for enabling digital transformation if collaboration is a skill, a culture or both?. The answer is likely “quite a bit”. Taking digital transformation as a theme itself, it opens the door on interpreting collaboration and how it manifests, bringing asynchronous and synchronous into the mix, where it is possible to collaborate at distance, without some key elements overtly being part of it (such as negotiation), but all still recognisably “collaboration”. If I were to commit on this one, for me it lean more into collaboration as a culture because that`s the mindset that will be needed to facilitate “good” digital collaboration, but the discussion is most definitely open.

So, back to my original question: Is collaboration a skill or a culture? As always in HE, the answer is a mixture but this editorial has aimed to shed a little more light of the interplay then between collaboration culture as it either helps or hinders collaboration skill practice and development. Have a read of the case studies, see if you agree or indeed, if you can spot a theme I did not.

Join the conversation at the Digital Culture Forum

One reply on “Collaboration: Skill or Culture?”

Very interesting observations here. I must admit I noticed a similar “issue” a decade or so ago, when the world of Web 2.0 opened up to us – with the chant of “Blogs & Wikis” ringing in our ears. The wiki was supposed to make everyone collaborate easily.. But I found scant evidence of these being used to great effect.. In the end I also came to a similar conclusion, that (online) collaboration using wikis was difficult to manage and work into summative assessments. And so the terminology “cooperation” seemed more meaningful. As ever these tools were just thrown out to unprepared students to just “go and collaborate” in your team project… Careful scaffolding and practice/modelling/micro-assessments is required – all the time. Even those platforms with very visible social media/chat/discussion tools, fail to enable cooperation or effective collaboration without plenty of help and ongoing use by academics; who can find the time to use them well. The world of online learning have been doing this well for decades (Etivities, etc). So it’s not impossible, but does require support and a change in mindset, & assessment practice.