Key principles for digital practice

Alejandro Armellini from University of Portsmouth shares how the university is using the lessons learned from the pandemic to design pedagogic approaches that support hybrid digital working.

Author : Alejandro Armellini

What exactly is the shift in culture and/or organisational practice that you wish to highlight?

The request for a full “return to normal” has been noticeable across large sections of staff and students for many months now. I wish to highlight the need to be more critical about that desire: going back to normal (i.e., established pre-pandemic practices) may actually not be such a good move. The University of Portsmouth’s Digital Success Plan for Learning and Teaching was built in 2021 on the premise that many of the lessons learned and practices developed since March 2020 should continue to form an integral part of our university’s chosen pedagogic identity. In other words, in terms of pedagogic design, teaching, learning and assessment practices and staff development (among other areas), going back to a “pre-Covid normal” is not an option.

Two key principles helped to guide our thinking in relation to digital practices:

- Good teaching is a solid starting point for meaningful, purposeful and innovative technology adoption.

- Content is not King. Context is. What matters is what students and tutors do with content, why, how, when and with whom.

At Portsmouth, we describe our institutional approach to learning and teaching as “blended and connected”, which means that our students engage with their studies

- through activities that enable them to take ownership of and critique new concepts, ideas and feedback;

- in and outside the classroom, synchronously and asynchronously, individually and in teams;

- for the development and application of subject knowledge, professional and digital skills.

The desire to revert back to a comfort zone, partly due to the exhaustion caused by almost two years of restrictions, including months of “emergency remote teaching”, should not get in the way of building our innovative, post-pandemic pedagogic future and identity.

What did ‘working well’ look like?

These case studies are meant to be about “examples of effective digital working” and “embedding digital change”. Interestingly, no definition of “digital working” is offered. At which point do working practices turn (or cease to be) “digital” in universities?

I would like to ask “what might ‘working well’ look like in the months and years ahead?”, and “what may work less well in the near future?” The answers, inevitably, need to be based on evidence gathered during the pandemic, but also over the years preceding it. They should not rely on bursts of enthusiasm about a particular tool, technology or approach, nor should they be driven by the often questionable proposals of technology vendors.

A good example is the synchronous hybrid or (so-called) hyflex classroom. In this environment, in-person students and lecturers attend campus-based sessions where remote learners also take part in real time, typically through a videoconferencing application. This article is not intended to conduct a review or critique of hyflex, on which studies are already available, but it is worth stressing that many universities have implemented hyflex pilots out of necessity rather than choice, in an attempt to “reach” (not necessarily “teach”) more students at the same time.

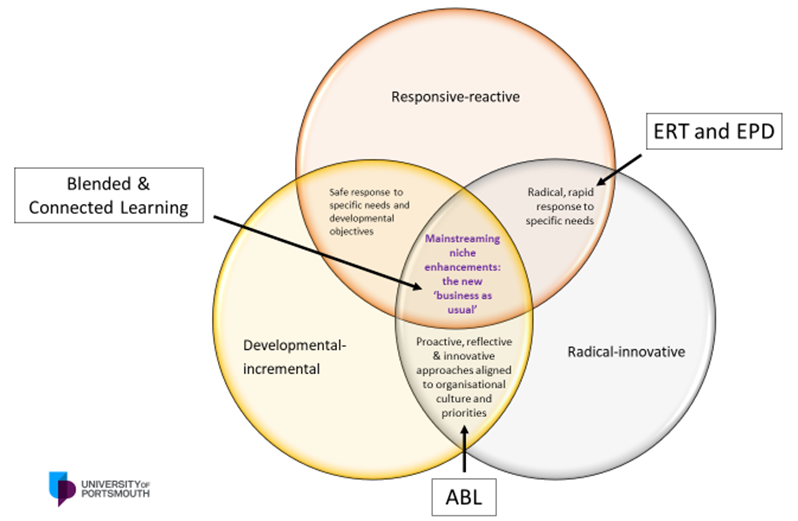

Modelling institutional pedagogic quality enhancement (figure 1) may help visualise what worked in the past and consider what may work well or less well in the future. The model uses three overlapping types of institutional initiatives: responsive-reactive (e.g., what universities had to do in response to Covid), developmental-incremental (‘slow burn’ changes from within the institutional culture) and radical-innovative (changes often seen as unexpected and requiring a generous appetite for risk). The centre of the model captures practices and approaches that have worked well in specific areas or niche contexts and puts them forward for further analysis and potential wider adoption. The figure maps four major initiatives onto the model (the first and last are specific to two universities):

- The introduction and scaling up of active blended learning (ABL) at the University of Northampton (2014-2018), where I was Dean of Learning and Teaching (see Padilla and Armellini, 2021, and Armellini, Teixeira Antunes and Howe, 2021).

- The shift to emergency remote teaching (ERT) across the sector in March 2020.

- The need to offer prompt emergency professional development (EPD) for university staff from March 2020 (Armellini and Padilla, forthcoming).

- Cementing blended and connected learning as Portsmouth’s pedagogic identity, and mainstreaming associated practices (ongoing, since early 2021).

How could practices be spread?

As we continue to live with Covid, we are operating in a learning and teaching environment characterised by lower physical proximity and lower synchronicity. Campus-based universities need to do more of what they were primarily doing pre-pandemic (namely face-to-face teaching) but also explore and research other forms of teaching, including creative and engaging student-centred blends, supported by the appropriate deployment of digital technologies. Earlier work on pedagogic transformation for learning innovation unknowingly prepared some institutions for the sudden changes that the pandemic required, as was the case with ABL at Northampton.

For good practices to spread, context-sensitive blends for learning and teaching should be conceptualised in more sophisticated, holistic and reflective ways than the simplistic “combination of face-to-face with online components” (see Armellini and Padilla, 2021, for a discussion on this). In particular, good asynchronous teaching practice (not the online “delivery of content”) is likely to continue to play a major role in any blend over the coming months and years.

One of the principles outlined at the start of this article refers to good teaching as a driver for purposeful technology use. Active, visible and engaged tutors are likely to sustain activity, visibility and engagement in their learners.

References

Armellini, A. & Padilla Rodriguez, B. C. (forthcoming). Emergency professional development in higher education: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. In R. Sharpe, S. Bennett and T. Varga-Atkins (Eds) Handbook for Digital Higher Education. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/handbook-of-digital-higher-education-9781800888487.html

Armellini, A. & Padilla Rodriguez, B. C. (2021). Active Blended Learning: Definition, Literature Review, and a Framework for Implementation. In B. C. Padilla Rodriguez & A. Armellini (Eds.), Cases on Active Blended Learning in Higher Education. IGI Global. https://www.igi-global.com/gateway/chapter/full-text-pdf/275671

Armellini, A., Teixeira Antunes, V. & Howe, R. (2021). Student perspectives on learning experiences in a Higher Education active blended learning context. Techtrends. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00593-w

Maxwell, R. & Armellini, A. (forthcoming). Academic engagement in pedagogic transformation. In M. D. Sankey, H. Huijser & R. Fitzgerald (Eds) Technology Enhanced Learning and the Virtual University. Springer.

Padilla Rodriguez, B. C. & Armellini, A. (Eds.). (2021). Cases on Active Blended Learning in Higher Education. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7856-8

Join the conversation at the Digital Culture Forum